Essay 5: Confederate Public History

Recognizing that inaccurate history often subtly promotes continuing white supremacy, the National Education Association (NEA) commissioned these articles and has posted some of them in slightly different form at its website. I thank Harry Lawson and others at NEA for the commission, for editorial suggestions, and for other assistance.

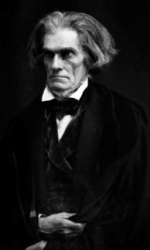

Across the South — and much of the North too — Confederate flags, monuments and names dot our landscape. After Dylann Roof’s June 2015 murders of nine African American church-goers in Charleston, South Carolina, many people began to question these memorials and symbols. A month later, Gov. Nikki Haley signed a bill removing the Confederate Battle Flag from South Carolina’s state capitol. Then Mayor Mitch Landrieu led New Orleans to take down three Confederate statues and a “White League” monument in that city. From Helena, Montana, to Orlando, Florida, citizens have been challenging other Confederate monuments. Americans are also questioning honors to other avowed racists, such as John C. Calhoun in Minneapolis, Orville Hubbard in Dearborn, and Edwin DeBarr at the University of Oklahoma.

These controversies offer wonderful teachable moments. Suddenly communities display new interest in U.S. history. Teachers can get students involved in researching the issues.

The main point to get across is that every monument is “a tale of two eras” — what it’s about and when it went up. A monument — or historical movie, play, or novel — may say nothing accurate about the former, but it always reveals something about the latter. After students realize this, they learn twice as much when they encounter the past on the landscape, on screen, or in print.

Consider South Carolina’s monument for its Gettysburg soldiers. It states, “Abiding faith in the sacredness of states rights provided their creed here.” An earlier essay in this series quoted the “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina.” Actually, the state’s leaders opposed states’ rights. So the monument is flatly wrong about the 1860s.

Students who research the stone learn that it went up in 1965. At that time, South Carolina’s leaders indeed believed “in the sacredness of states rights,” which they used to try to stave off U.S. insistence that they desegregate their schools and let African Americans vote. So the monument has something to teach about the 1960s.

The three immediately antecedent essays in this series show that teachers cannot present the Confederacy and the Union as moral equals without harming historical fact. This can be hard to handle with white parents and students whose ancestors fought for the Confederacy. We must grant that many individuals fought because they were told to, friends were joining, or to protect against invasion. Many were not fighting for slavery on a personal level. Nevertheless, they were fighting for the Confederacy, whose reason for existence was slavery in the service of white supremacy.

Teachers need to disabuse white students of their affection for the Confederacy. Otherwise, we will continue to see white students abusing these symbols and creating their own examples of Confederate public history, as some did in Bloomington, Indiana, in 2016. There, students countered LGBTQ students organizing rainbow flag displays of pride by coming to school the next day wearing Confederate battle flag symbols. Gay Straight Alliance members took issue with the false equivalency between the rainbow flag and the Confederate flag, pointing out that one is a symbol of support and inclusion and the other represents a long history of racial violence and oppression. The LGBTQ students and their allies used this teachable moment to meet with the superintendent resulting in a policy banning the Confederate flag on campus.

If you have no local history controversies, you can get students doing local history anyway. Who should get a historical marker in your community? Whose statue or monument deserves at least a corrective marker, if not full removal? Even when students don’t actually change the landscape, they learn many skills when they actually do history like this.

Essential Reading

- Loewen, “Ten Questions for Yale President Peter Salovey,” Chronicle of Higher Education, 6/10/2016, B11-13; also at History News Network, historynewsnetwork.org/blog/153767, treats the issue of naming places — in this case a dormitory — for famous dead people who did bad things, in this case John C. Calhoun.

- Right after he took down the three Confederate monuments in New Orleans, Mayor Mitch Landrieu explained why, in a speech he titled, simply, “Truth.” It went viral. You can read and see it here: http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/166085.

All essays in the Correct(ed) series:

Introducing the Series

Essay 2: How to Teach Slavery

Essay 3: How to Teach Secession

Essay 4: Teaching about the Confederacy and Race Relations

Essay 5: Confederate Public History

Essay 6: Reconstruction

Essay 7: Getting History Right Can Decrease Racism Toward Mexican Americans

Essay 8: Problematic Words about Native Americans

Essay 9: How and When Did the First People Get Here?

Essay 10: The Pantheon of Explorers

Essay 11: Columbus Day

Essay 12: How Thanksgiving Helps Keep Us Ethnocentric

Essay 13: American Indians as Mascots

Essay 14: How to Teach the Nadir of Race Relations

Essay 15: Teaching the Civil Rights Movement

Essay 16: Getting Students Thinking about the Future