Essay 15: Teaching the Civil Rights Movement

Recognizing that inaccurate history often subtly promotes continuing white supremacy, the National Education Association (NEA) commissioned these articles and has posted some of them in slightly different form at its website. I thank Harry Lawson and others at NEA for the commission, for editorial suggestions, and for other assistance.

What are the underlying causes that made the Civil Rights Movement possible? Can students show that the Movement was far more than one man, even if a holiday is named for him? What are some ways to bring the Movement alive in the classroom and relate it to the present?

Around 1940, three social processes started undermining the Nadir of race relations. First was African Americans’ growing political influence. During the Nadir, Southern states had passed new constitutions that removed them from citizenship. The “Great Migration” from the South freed the migrants to vote again. Moreover, owing to all the sundown towns in the North, the newcomers wound up in a handful of cities where, owing to residential segregation, they wound up in just one neighborhood. This residential concentration hurt race relations, but it did enable African Americans to elect a handful of aldermen and state representatives. Now white elected officials had good reason not to disregard black interests completely or insult African Americans with offensive terms.

Second, imperialism was dying. As soon as World War II ended, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia demanded independence from the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands. Soon Ghana and other African colonies followed suit. Maintaining overt racism like formal segregation and sundown towns did not help the U.S. win the allegiance of these new countries in a contest with the Soviet bloc.

Third came the Third Reich. Every country demonizes its opponents in war, but Germany made it easy. When Americans learned what Nazis had done to their Jewish and Rom (“Gypsy”) minorities, they were horrified that such savage treatment would be meted out to people we would define “white.”

As the Nadir intensified, African Americans had chafed at the loss of their rights. Now they began to feel that challenges to racism might succeed. Truman’s order desegregating the Armed Forces provided one signal. Jackie Robinson’s entry into Major League Baseball furnished another. With a thousand little actions, African Americans now confronted the system of White supremacy.

Too many students today know Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and little else. King was important, but across the South — across the North as well — local residents played the key roles. Some are still available to guest speak. Students can learn about others from oral histories, friends and descendants, and newspaper accounts. Students might then propose a historical marker for one or for an event. If they attend a school district formerly segregated by law, students can study the year when desegregation occurred (if it did). Maybe their own school deserves a historical marker; part of its history would be how it desegregated. Many private schools started or expanded when the public schools desegregated; this history, too, deserves a marker.

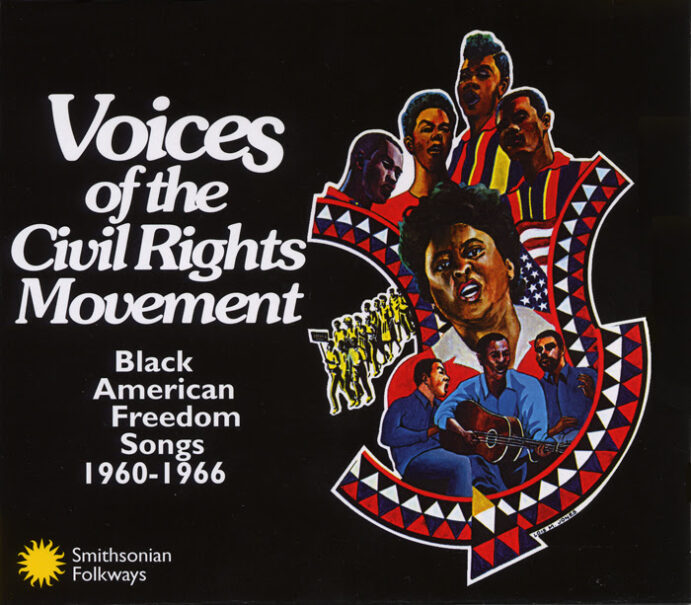

No cause made more use of music than the Civil Rights Movement. Singing civil rights songs together links students to the movement and can spur them to research the role each song played. Sadly, many students today don’t know the words even to “We Shall Overcome.” From the Smithsonian collection of Civil Rights songs, they can sing along to two versions of “We Shall Overcome.” Then invite them to create new verses about issues of today — local or national.

One verse goes, “The truth shall make us free.” As the final essay in this series will show, I believe truth is on the side of justice.

Essential Reading and Listening

- If there was no Civil Rights Movement in your area, study the website “Voices of the Civil Rights Movement,” voicesofthecivilrightsmovement.com. You can make use of its video interviews of participants in the movement.

- “Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: Black American Freedom Songs 1960-1966,” folkways.si.edu/voices-of-the-civil-rights-movement-black-american-freedom-songs-1960-1966/african-american-music-documentary-struggle-protest/album/smithsonian. Besides “We Shall Overcome,” useful songs include “We’ll Never Turn Back,” “Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom,” “Which Side Are You On?” “Oh, Freedom,” “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round,” and “We Shall Not Be Moved.”

- “Our Stories,” crmvet.org/nars/narshome.htm, offers a mass of interviews, some oral, some visual, some transcripts, with members of the Civil Rights Movement.

All essays in the Correct(ed) series:

Introducing the Series

Essay 2: How to Teach Slavery

Essay 3: How to Teach Secession

Essay 4: Teaching about the Confederacy and Race Relations

Essay 5: Confederate Public History

Essay 6: Reconstruction

Essay 7: Getting History Right Can Decrease Racism Toward Mexican Americans

Essay 8: Problematic Words about Native Americans

Essay 9: How and When Did the First People Get Here?

Essay 10: The Pantheon of Explorers

Essay 11: Columbus Day

Essay 12: How Thanksgiving Helps Keep Us Ethnocentric

Essay 13: American Indians as Mascots

Essay 14: How to Teach the Nadir of Race Relations

Essay 15: Teaching the Civil Rights Movement

Essay 16: Getting Students Thinking about the Future