We have tried hard to get a photo of a typical sundown town sign, but so far without success. A graduate of the U of TN had a roommate from a sundown town who was proud of a photo of her taken next to her town’s sundown town sign, when it was still up. But Loewen couldn’t persuade the former roommate, no longer on good terms with her roommate, to ask her for a copy. A man in Manning, IA, has a grandmother who had taken a photo of Manning’s SDT sign. He was going to send an image of it, but we were too late; the grandmother, going senile, had thrown out all her photos, disappointing her family of course, and also us. The sign itself in Pekin, IL, is said to be extant, but in the custody of the KKK; we don’t think they will release it to us. And so it goes. But if you have a sign or photo thereof, please let us know, soonest! Thank you.

Early Sundown Town Illustrations

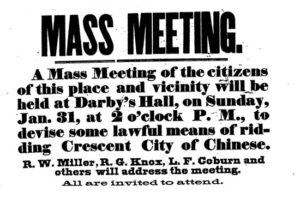

Chinese Americans had lived in Crescent City, California, near the Oregon line, since at least the 1870s. The meeting advertised on this broadside was the first of a series lasting until mid-March, 1886. Eventually “lawful” was dropped and a mob forced the Chinese to depart on three sailing vessels bound for San Francisco. Whites in Humboldt County, the next county south, had already expelled 320 Chinese Americans from Eureka in 1885. In 1886 they drove Chinese from Arcata, Ferndale, Fortuna, Rohnerville, and Trinidad.

In 1906, whites in Crescent City, California, near the Oregon line, drove their last remaining Chinese Americans, these cannery workers, onto boxcars, and forced them to flee, leaving their belongings behind. No Chinese Americans returned to Humboldt Bay until the 1950s.

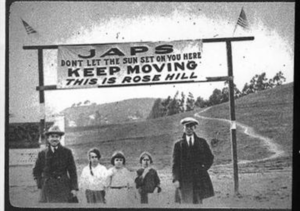

Rose Hill, often spelled with a final s, is an unincorporated “Census Designated Place” near Los Angeles that declared itself a sundown town vis-à-vis Japanese Americans in 1921. We suspect it also kept out African Americans; even in 2010 only 9 Blacks lived there.

In 1923, the Hollywood Protective Association formed to “Keep Hollywood white” and drive out the “yellow menace.” One member, Mrs. B. G. Miller, put this huge poster on her house and got newspaper attention for it and her cause.

After Comanche and Hamilton counties, Texas, drove out their African Americans in 1886, Alec and Mourn Gentry were the only two who “have been permitted to reside in this section,” in the words of the 1958 Hamilton County centennial history. “‘Uncle Alec’ and ‘Aunt Mourn’ lived to a ripe old age…. They were Gentry Negroes, and former slaves of Capt. F. B. Gentry…” They were no one’s uncle or aunt in Hamilton County, of course; these are terms of quasi-respect whites used during the Nadir for older African Americans to avoid “Mr.” or “Mrs.” (Aunt Jemima Syrup and Uncle Ben’s Rice linger as vestiges of this practice.)

This house stands in the neighborhood called “the Black Hills,” home to African Americans in Pinckneyville, Illinois, until they were driven out around 1928. A white woman born across the street in 1947 recalls being teased in school “for living in niggertown.” This house was formerly the black school before whites took it.

This striking granite tombstone commemorates Anna Pelley, who was murdered in Cairo, Illinois, in November, 1909. Her supposed killer, Will James, was lynched in retaliation. Afterward, residents in her hometown of Anna responded by driving all African Americans out of the town. Public subscription then paid for this tombstone. At least as late as 2002, adolescents in Anna still paid their respects at this site, a rite that helped maintain Anna as a sundown town.

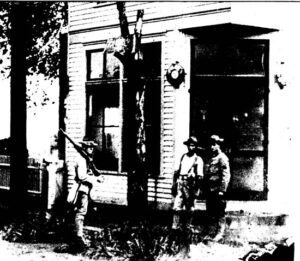

In 1908, white mobs in Springfield, Illinois, tried to turn it into a sundown town. They failed, partly because Springfield is the state capital, so the governor had to take notice and call out state National Guard. Here are three Guardsmen in front of a tavern, posing next to a tree. The day before, the white mob had hung an old African Amereican from that tree. His crime? He had lived for half a century with his white wife. Does the tree look strange? That’s because its smaller branches have been hacked off and broken up so members of the mob could have souvenirs of their work.

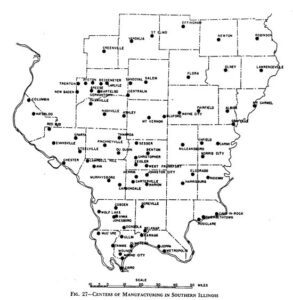

In 1952 Charles Colby mapped 80 communities in Southern Illinois, including every larger city, many towns, and some hamlets, all chosen because they had factories. Of his 80 towns, 55 or 69% are suspected sundown towns, “all-white” for decades. Among these 55, I confirmed the racial policies of 52, and of those 52, 51 (all but Newton) were sundown towns. The dotted line at the bottom is the “dead line,” north of which African Americans were not allowed to live (except in the unbolded towns). South of this line, cotton was the major crop; white landowners employed black labor, following the Southern tradition of hierarchical race relations rather than Northern sundown policies. All eight towns below this line let African Americans live in them. Among the 72 towns above the line, only 17, just 24%, did.

This sign still stands, painted on a rock face just west of Liberty, Tennessee. The symbol, a black mule, was used by residents of sundown towns in Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee to warn African Americans to “get their black ass” outside the city limits by sundown. Margaret Alam photographed this example, in 2003.

In 1914, Villa Grove, Illinois, put up this water tower. Sometime thereafter, the town mounted this siren on it that sounded at 6 PM to warn African Americans to get beyond the city limits, until about 1998. At that point, owing to complaints about the noise from residents living near the tower, it stopped, but Villa Grove has not made a clear statement as to its sundown town policy. Loewen has found maybe twenty more towns with 6PM sirens, about half of which sounded to tell Blacks (or in two cases Native Americans) to be gone.

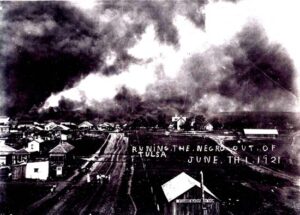

On June 1, 1921, whites tried to make Tulsa, Oklahoma, a sundown town. As part of the attack, deputized white men raided a munitions dump, commandeered five airplanes, and dropped dynamite onto the black community, making it the only place in the contiguous United States ever to undergo aerial bombardment. Like efforts to expel blacks from other large cities, the Tulsa mob failed; the job was simply too large. But it killed at least 100 Black residents and destroyed a thriving business district called “Black Wall Street.”

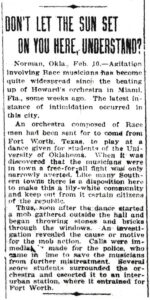

University of Oklahoma students invited a black orchestra to play for their dance, but citizens of Norman intervened because the musicians violated Norman’s sundown rule. Dances are after dark, of course, and residents stoned the fraternity house and threatened the lives of the band. This 1922 story in the Chicago Defender uses “Race” where we would use “Black.”

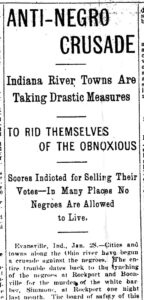

This report from Evansville tells of a wave of anti-black actions in southwestern Indiana in 1901, triggered by “the lynching of the Negroes at Rockport and Boonville for the murder of the white barber.” Only contagion can explain how the murder of one barber could prompt three lynchings in Rockport, one in Boonville, and “vigilance committees” to drive African Americans from at least five other towns.

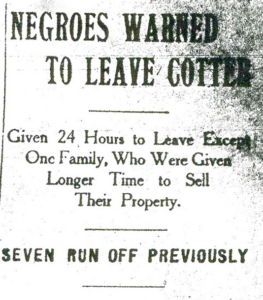

Sometimes, local newspapers did tell when whites drove out entire black communities, such as in Cotter, in the Arkansas Ozarks, in 1906.

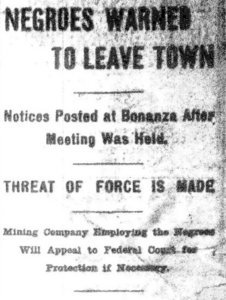

In 1904, Whites drove out the Black population of Bonanza, in western Arkansas. The small town still had no black households as late as 2000.

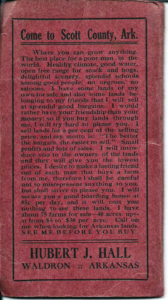

This ad seeking white buyers for land in Scott County, AR, openly brags “no negroes, no saloons.”

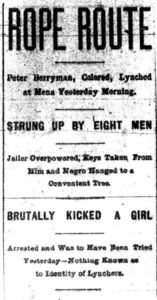

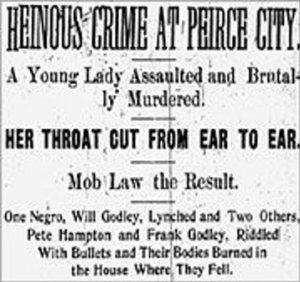

Often a lynching led to a town going sundown, as its Black families fear for their lives. This incident happened in Mena, AR, in 1901.

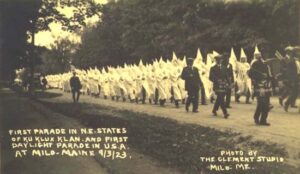

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan (second version) had its heyday, becoming briefly the largest fraternal organization in the United States. It created new sundown towns by terrifying and driving out the few Black residents in various towns, and it also held huge rallies in towns that already were sundown.

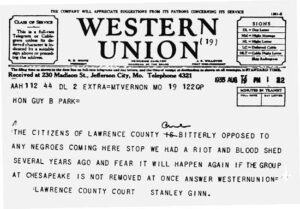

Some riots that drove African Americans from small towns left documentary hints, such as the telegram below. In Missouri, a black Civilian Conservation Corps unit was scheduled to work in Lawrence County in 1935, prompting this telegram to Gov. Guy Park. Loewen thinks the “riot and blood shed several years ago” alludes to a riot in Mt. Vernon, Missouri, in 1906, but it may refer to a more recent event. The telegram worked: the camp was moved; and Lawrence County’s black population declined to just 21 by 1950.

This August 22, 1901, article from the Lawrence Chieftain (Mt. Vernon, Mo.) basically justified the lynchings and expulsion of the Black population.

Later Sundown Town Illustrations

Although not a sundown town, this White neighborhood In Detroit tried to keep African Americans out of a public Housing project, Sojourner Truth Homes, that had actually been built for Blacks. They failed, but the sundown suburbs of Detroit stayed all-White.

Whites demonstrated to keep Cuyahoga Falls, sometimes nicknamed “Caucasian Falls,” a sundown town.

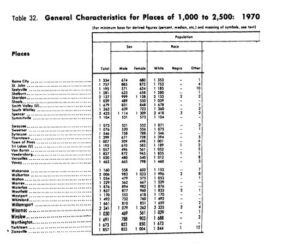

This page from the 1970 census shows how widespread all-white towns — probably sundown towns — have been in Indiana. 26 of these 34 had not a single black resident, and bearing in mind that sundown towns often allowed an exception for one black family, we cannot be sure that any of the 34 admitted African Americans. Indiana had twenty times as many African Americans as “Others” in 1970, yet Others lived much more widely.

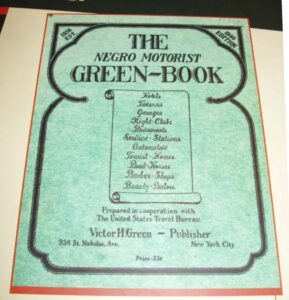

To avoid sundown towns and negotiate travel without danger or embarrassment, African Americans produced guidebooks such as Travelguide: Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation and this Negro Motorist Green Book. They listed hotels, restaurants, auto repair shops, etc., that would serve black travelers.

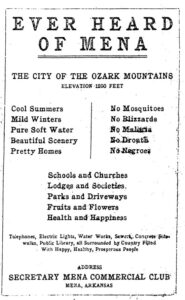

In the mid-1920s, Mena, county seat of Polk County, Arkansas, competed for [white] residents and tourists by advertising what it had and what it did not have. The sentiment hardly died in the 1920s. A 1980 article, “The Real Polk County,” began, “It is not an uncommon experience in Polk County to hear a newcomer remark that he chose to move here because of ‘low taxes and no niggers.'”

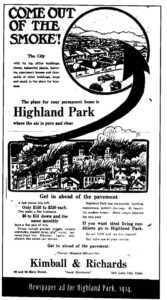

In 1914, developers of Highland Park near Salt Lake City had appealed to would-be homebuyers to leave behind the problems of the city, like its smoke. By 1919, the appeal had become racial. Even today, the most prestigious suburbs are often those with the lowest proportions of African Americans.

A street barrier marks the border between North Brentwood, a black community, and Brentwood, Maryland, a sundown suburb into the 1960s. Struck by the absence of any social class difference between homes on both sides of the barrier, Loewen asked Denise Thomas, who grew up in North Brentwood in the 1950s, “What kept people from North Brentwood from crossing that line?” “KKK!” was her heartfelt answer. By that she meant not only the Klan, which burned crosses in North Brentwood, but also many other instances of harassment. “They threw things at us, called us ‘nigger,’ ‘spook,’ all kind of things.” “The white children?” Loewen asked. “Uh-huh,” she affirmed, “and the adults.”

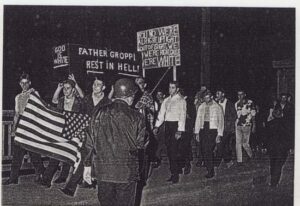

Father Groppi was a Catholic priest in Milwaukee who led marches on behalf of African Americans, who were kept out of most suburbs and many neighborhoods. These whites exemplify the fierce opposition he and his marchers aroused. Is God white?

According to historian Kenneth Jackson, “the most conspicuous city-suburban contrast in the U.S. runs along Detroit’s Alter Road” separating Detroit from Grosse Pointe. Just across the line is this park, but Detroit children cannot play on its playground equipment. “It’s not fair,” observed Reginald Pickins, who grew up less than 50 feet from the border. “Why should we have to have passes to go into their parks? They don’t need passes for ours.” Loewen thinks tourists from towns that do this should not be allowed into New York City’s Central Park, Detroit’s Belle Isle, or any other city parks, but he admits there would be no easy way to enforce such a prohibition. Grosse Pointe has no problem, of course: if the intruders are Black, they’re unlikely to be from Grosse Pointe, so keep them out.

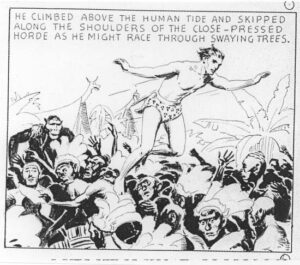

Tarzan, the white man who mastered the African jungle, was born in one sundown suburb, Oak Park, Illinois, where his creator, Edgar Rice Burroughs, wrote the first Tarzan books, and gave birth to another, when Burroughs used the proceeds from his novels, movies, and long-running comic strip to create Tarzana, California. In this 1934 strip, “the island savages” flee “in terror” from jungle creatures, “believing the beasts were demons conjured up by Tarzan.” The strip literally shows white supremacy: Tarzan is more intelligent, courageous, and moral than the black “savages,” whom he literally walks all over.